The mystery of Dr. P., first part

The mystery of Dr. P.

He was a lancer, and Zosia. This ladies, if you can't think, you won't be able to do anything. Do what you want, the horse will die anyway. In a scout uniform for war. Put that statistic away or you'll get locked up. Let what you want happen

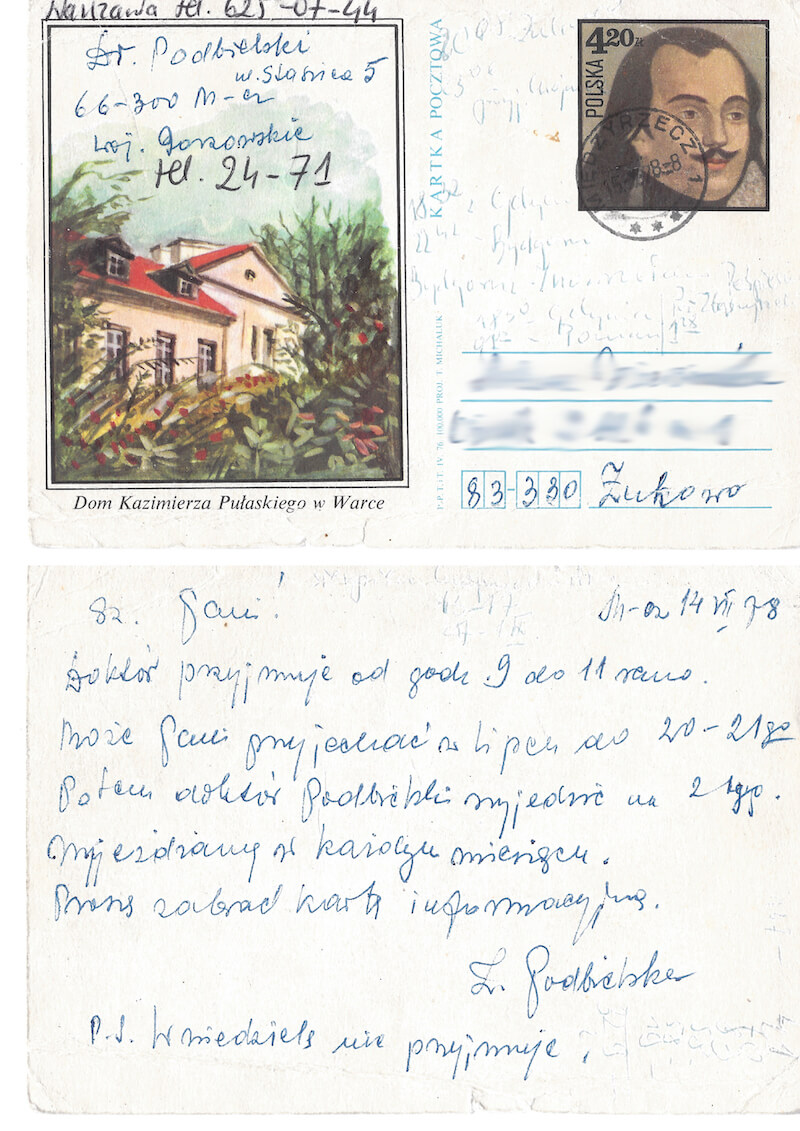

Full of admiration, I watch and listen to how Mr. and Mrs. Podbielski, patiently and with no visible signs of fatigue, receive at their apartment those pilgrimages of people from all over Poland, who come to Miedzyrzecz for the medicine shrouded in legend, which is their hope and, as often, their last chance. It makes me wonder where they get so much indefatigable energy. And I think I know: it comes from a benevolent openness to the affairs of the world and other people in particular. A strong inner conviction, in which they constantly reassure each other, that everyone here has some important mission in life to fulfill, in order to fulfill it they must want it very much and must be able to do it.

For both of them, this mission in life has become a matter of "their" drug. A drug that for thirty years they have been producing and distributing on their own, although it has become, one could already say, public property despite the fact that it is not officially accepted, because such acceptance is a matter of a long and arduous struggle. Doctor of veterinary sciences Tadeusz Podbielski was at times already inclined to doubt the success and meaning of this struggle. Then Sophie, his most faithful life companion came to his aid with words of encouragement and encouragement: don't break down, victory is ahead. But there were also times, when he went astray in this work, disregarding his own health, she tried to put the brakes on him a bit: slow down, rest, after all, a man has his endurance. A few years ago, she began to write a book about him. It was to be a long story about living an active life, a constant struggle against adversity and breaking the artificial barriers of ossified thinking, which is often dressed in the robes of illusory, quasi-scientific schemes, canons that get in the way of moving forward. She wrote the beginning, there is no time for the continuation. This book is written by life itself. Once in the 1920s, when he was a student at a Lomza high school, while she was a student at a teachers' seminary and a girl scout, they performed in an amateur theater. To this day they remember those patriotic performances evoking an ovation from an audience of a hundred, when he performed, for example, the role of a convict in " The Tenth Pavilion." Those touching scenes of saying goodbye to his mother, when his mother was played by his future wife. They traveled around the villages with "Krysia the Forester" or with " Zosia and the Lancer," in which he was the lancer and she was, of course, Zosia. Later, when she became a teacher in Kolno (and, of course, a troop leader in the scouting movement, with this interest in scouting, still brought up somewhere in Poltava, Russia, where her family was evacuated from Suwalki in 1917, remaining to this day), and he became a student of the veterinary faculty at the University of Warsaw, these their patriotic raptures matured, fulfilled in a new way.

Now, when Dr. Podbielski recalls his student days, the words of Professor W. often come to mind. The professor had no time for anything. Absorbed in some social or state activity, he often didn't show up for lectures, skipped classes; hence, he requires mainly independent work of students, while when he came, he said: " I just want to teach you to think. This, sir, if you don't know how to think, you won't know anything, and if you know how to think, you will write books yourself ". The doctor says that the university gave him a broader outlook on life, and the discipline that is essential in this life was taught to him by the cavalry cadetship in Grudziądz, and later by service in the regiment. And here the young veterinary graduate tried for the first time in his life to go beyond the learned formulas from books.

Once upon a time, one horse in the regiment fell ill with tetanus. The horse was beautiful, the prospects for a cure were nil, a council was convened and the verdict was made: shoot.

- Major," said Podbielski to the commander. - I would like to experiment. Can you? I will try to cure him. - Do what you want, the horse will die anyway.

A young veterinarian lived next to the ambulance. The horse was hanging suspended from a brace, practically doomed to die. - I said to one of the cannoneers: you have a comfortable chair here, sit down and watch. If this horse urinates, stand a dish and catch the urine. And so it happened. Later I filter this urine, strain it into a syringe and give the horse an injection of it. What was it? It was autourotherapy. At that time, hemotherapy was fashionable, taking blood in one place and injecting it in another. Meanwhile, the horse fighting the disease produced antitoxins, antibodies. They were in the urine. It was necessary to try to treat him with these. Well, and indeed the horse recovered.

This was the first independent attempt to seek new methods of treating animals, to go beyond established practices. The next, although already of a different kind, will be undertaken by Dr. Podbielski after the war in Miedzyrzecz. But here he would also come already rich in experience in working with the countryside. In the 1930s, as a young veterinarian in Lomza, then Kolno, Kurpie, he traveled to farmers with lectures, organized dairy cooperatives, one could say - he helped organize modern agriculture based on rational principles. This was a few kilometers from the German border, where one of the important elements of this work was the development of patriotism. When they dedicated and opened the new dairy, the peasants donated two machine guns to the army, some donated their short weapons for its use, and Podbielski, as chairman of the supervisory board, gave a patriotic speech. " We built this dairy by joint efforts, but let's stick together boys, still together, because the enemy is close and preparing for war. We will still regain what is ours " - he was ahead of history. September 1939 was soon to follow.

Podbielski was called up to the army. What was his surprise when one day his wife Sophia, wearing a scout uniform, also followed him to the unit where he was serving. She would not leave him, she said to herself, took his backpack, found him and accompanied him all the time in that great retreat of the troops, then again the march on Warsaw, as a nurse. Later, when he was locked up by the Germans in a transit camp, she moved heaven and earth to get him out of there. She did this with the help of a German named Paluszek, who was the orderly of an officer from some auxiliary service there, someone named Altman. With this Paluszek she traveled from one important Wehrmacht cone to another, from town to town, until she got her way. But then again, what won't Zofia Podbielska, née Mogilnicka, of the Lubicz coat of arms, whose mother at home was Bagińska, of the Ślepowron coat of arms, accomplish?

Tadeusz Podbielski arrived in Miedzyrzecz on July 10, 1945, "I was directed here," he says, "by the Provincial Land Office in Poznan in order to take possession of these lands by the Polish state administration after 130 years of captivity and to organize veterinary services. I was the only veterinarian. Poor here was the economy in the beginning. A few dozen cows in the district, some horses, and the population was constantly flowing in from across the Bug River, from Poznan, Kielce..., took over the farms. After the Potsdam Conference, the Red Army drove large numbers of cattle and horses through the district beyond the Oder River, to Germany, to feed the soldiers. Well, some of these lame, etc. stayed here. These lame horses were caught, cured and distributed later to the settlers. The former foragers, farmhands who used to serve in the large estates of the heirs, took to the economy well. This developed from 1948.

For example, in Sierczno, one such farmer, when he came to the market in Miedzyrzecz, the pair of horses at his place was already so beautiful that when he rode, it seemed as if the count himself was riding, proudly. These horses walked beautifully. To these horses two foals, later he was already breeding five, six cows, and so the county's breeding statistics grew. But in the forty-eighth came collectivization, good farmers were considered kulaks and were driven to cooperatives. So again one time I meet this farmer from Sierczynek, and I knew everyone here, and I ask him what's up, and he says to me: Doctor, I'm quitting this farm, and it's beautiful, it's heartbreaking. I farmhand from my grandfather's great-grandfather worked in these heirs, more than once I got hit on the back with a pick or a stick, but it was less painful than now, when I was called a kulak, an exploiter and an enemy of People's Poland. Me, a kulak? And I liquidated.

And so, one by one, others liquidated their farms, while there were fewer and fewer cows also in calf, and sows in stock. And just as before the statistics, the breeding bars were going up, now there was a sharp decline. They organized meetings, an activist from Cegielski in Poznan and other party activists came and said how to organize these cooperatives here, because the kulaks around, and I say that breeding is falling and I pull out my statistics. And they at me that the doctor insists on kulaks, and they are enemies of the people. Well, and one to me quietly: doctor, hide that statistic, or they will lock you up.

So Podbielski fights numerous animal diseases, cures them, but he also cares about livestock breeding, so he doesn't miss the then widespread struggle for the collectivization of agriculture. As much as he can, he tries to stamp out drunkenness and dishonesty among his co-workers, with which, as a non-partisan at the time, he exposes himself to the local authorities, who are also at the center of the class struggle. He exposed himself because this particular co-worker was a party member. He was called by the secretary to clarify the matter, and in the end he said this: " We would have done a long time with you, but you are a useful man." It was difficult to work in such an atmosphere, but Podbielski never broke down, he honestly did what he was supposed to do and for which he was valued. He was valued by the authorities and valued by the farmers, whom he helped as much as he could. And the peasants would come and complain: " Something is wrong, doctor, the cows are losing milk, they are thin and don't chew". A lot of these cows had to be sent to slaughter. But Dr. Podbielski then began to wonder what could be the cause, why are these cows so sick? Every cow must be accounted for, because the class enemy was not asleep, and too much attrition could be treated as sabotage. This needs to be investigated on the spot.

So he went to Great Birch, where this problem was most acute, and took samples of the local water, hay, grass and soil, and his wife took this to the Department of Hygiene in Poznan for testing. The results of the analysis turned out to be extremely interesting: significant deficiencies of cobalt and copper, not much manganese. The lack of many essential minerals in the soil and feed is the cause of animal diseases, he thought. How to make up for these deficiencies? He searched for several months for cobalt and other ingredients, traveling to Warsaw, Gliwice, and Gdansk until he found what he needed. But once he had the cobalt, of course, along with instructions that it is a poisonous agent and is only used in dyeing. So if he wants to use it to treat cows, he needs to start experimenting. How? Now I admit that in the beginning he worked similarly to Pasteur or Koch. He prepared a solution that had a concentration of the element's content in the body and decided to drink it himself. - Let whatever happens," he said. - And Zosia saw that I was drinking it, this poison, and drank it too. We must be together, she decided.

Bronislaw Slomka